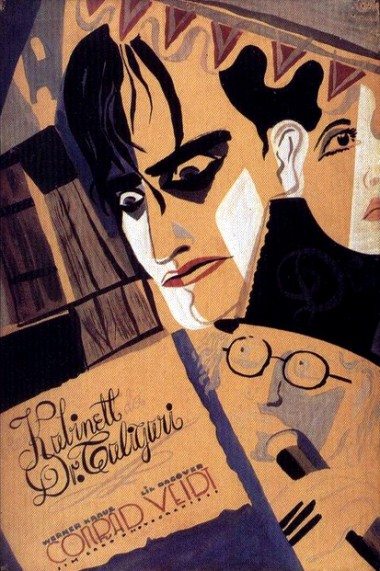

During the days of the Weimar Republic, German filmmakers began to embrace and explore a style of filmmaking that would come to be known as German Expressionism. This style was a stark contrast to the films that had been produced up until that point, especially films being produced by the U.S. Among the first films to be produced in this style was 1919’s “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” by Robert Wiene.

The film follows the tale of tormented lovers who have fallen victim to the nefarious Dr. Caligari and his somnambulist Cesare. The twist ending reveals the lovers and, in fact, Cesare, are all members of an insane asylum and Dr. Caligari is actually the head of the asylum, and the sets and makeup reflect the characters’ states of mind. The sets are dynamic, angular and jagged, giving an atmosphere of unease. Thick, black lines dominate the background, and although the sets look like sets (rather than actual cities and buildings), they are constructed in such a way that they show depth and dimension. Even the makeup is dark and unnerving, from the dark rings under Cesare’s eyes to Jane’s black Cupid’s bow lips, to the dark lines on Caligari’s gloves and hairline.

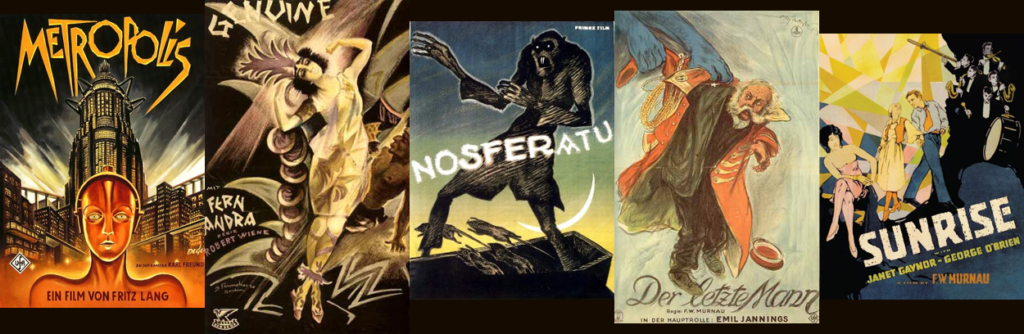

This concept of Expressionism was used again by Wiene in his sophomore production “Genuine: Tale of a Vampire,” though it was less successful than “Caligari.” But Expressionism didn’t end with “Genuine.” The stark, angular style and psychologically-focused storylines were adopted by Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau and applied to their own works. Murnau continued the tradition with his own psychological thriller and horror films, including “Nosferatu” (which we talked about in a previous post), “The Last Laugh” and even the emotional and beautiful “Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans.” And Lang added a futuristic element to the stylized sets when he explored the dystopian reality of “Metropolis.”

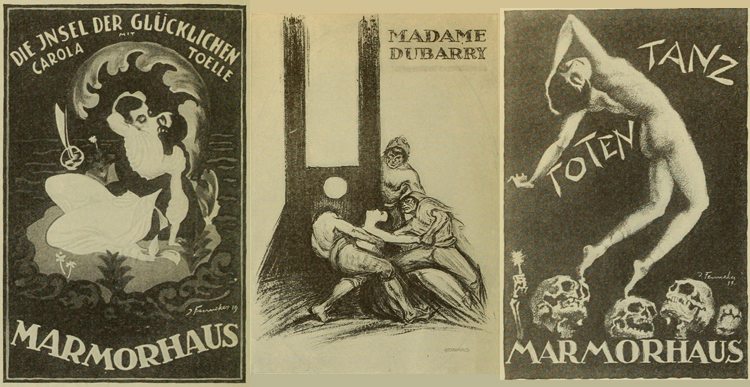

Of course, this dark style was also reflected in the artwork for these films and in the early ‘20s, U.S. censors were quick to object to their associated posters. Following WWI, the U.S. was reluctant to import German-made productions and this, no doubt influenced their attitude towards the German Expressionist style. (After all, many of the films being turned out by Hollywood revolved around the image of the evil Kaiser.) One writer for the fan magazine Photoplay commented on this style of poster saying rather nastily, “We can only wonder what our Censors would say if they were used on our billboards to exlpoit the ‘alarming invasion’ of this country by — as far as we know, some half-dozen — German films.”

By the time “Metropolis” and “Sunrise” were released just before the dawn of the talkie era, however, U.S. audiences and studios were eager to see offerings from the likes of Lang and Murnau. Photoplay hailed “Metropolis” as “A glimpse into the future… Pictured with such amazing realism and with such startling photographic effects that it will leave you breathless.” That included images like this that a few years earlier would have terrified and disturbed the censors and the public.

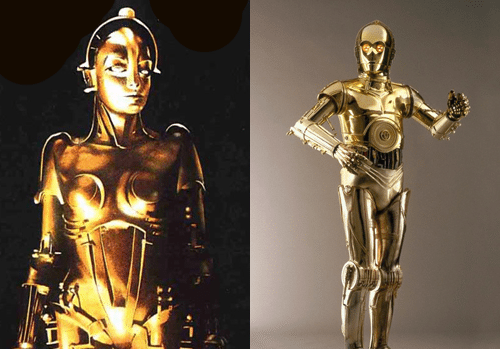

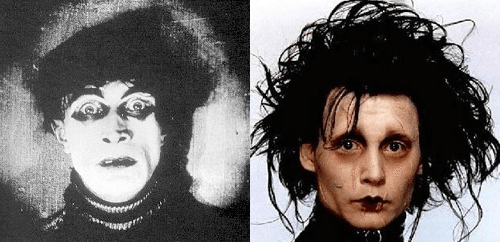

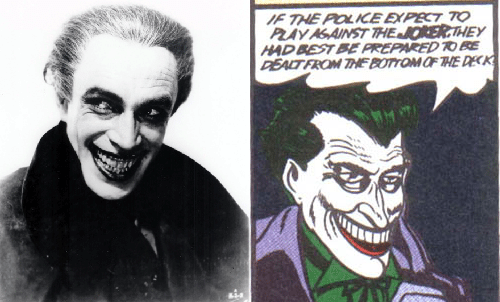

Now, of course, these films and their accompanying styles and artwork are hailed as some of the most iconic of all time. They’ve been referenced and copied time and time again in countless films, advertisements and music videos. The style of the Maschinenmensch (sometimes referred to as Parody or False Maria) served as inspiration for generations of androids to come, including that most famous of droids C-3PO, Conrad Veidt’s appearance in”Dr. Caligari” served as inspiration for Johnny Depp’s appearance in”Edward Scissorhands,” and Veidt’s appearance in “The Man Who Laughs” served as inspiration for The Joker.

Think reboots of Hollywood blockbusters are a new phenomenon? Think again. We discuss three silent films that found new life rebooted as talkies here.

And if you’re new to our silent film series, be sure to check out our past installments. Want to dive deeper into the world of silent film? Keep up with my posts over on Curtains or on Chicago Nitrate.