If you’re finding yourself frustrated by the sheer amount of remakes and reboots produced by Hollywood in recent years, you might be surprised to know that it’s not a new phenomenon.

Ever since the days of silent film, directors and studio execs have been looking at pre-existing work for inspiration. Popular books and plays were often quickly and easily adapted to film and usually resulted in a fair amount of audience interest. This is why, for example, there are so many silent versions of “The Wizard of Oz” and “Alice in Wonderland.” As more and more films were made, and technology and cinematography advanced, directors and execs began to look back to early films and remake them. Although they existed during the days of silent film, remakes became increasingly more common when the silent era ended and the talkies began to take hold.

The first days of sound film were shaky at best. Although “The Jazz Singer,” the first “talking” feature, debuted in 1927, many studios and stars didn’t completely make the jump to talking pictures for years. Most theaters weren’t equipped to show talkies and wouldn’t be for quite some time. As a result, execs were hesitant to try anything too experimental or risky for fear that it wouldn’t pay off. The solution? Remake silent films that audiences loved and toss in some dialogue. The studios already held the rights to the films and sometimes the original film’s stars were still under contract.

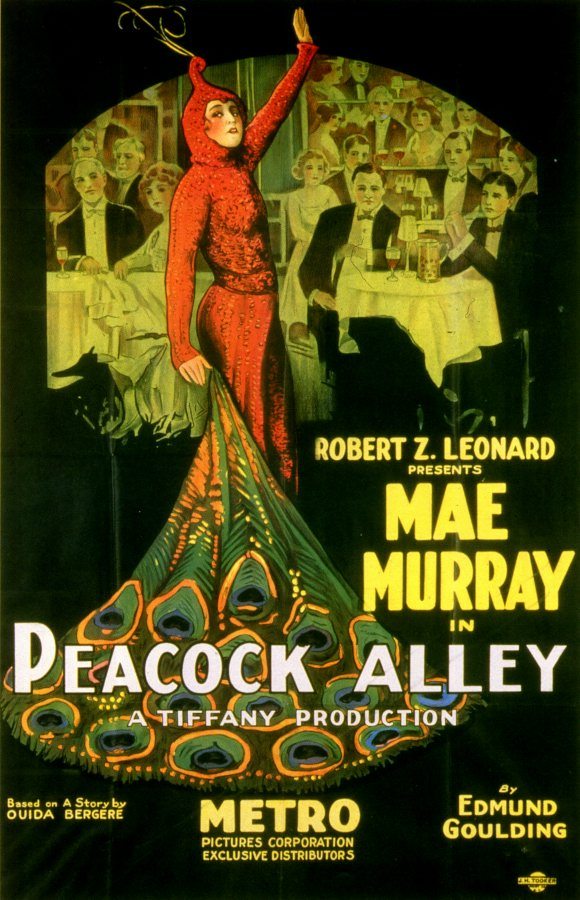

Silent star Mae Murray was well known for her over-the-top acting and her risque costumes — both of which were highlighted in the film “Peacock Alley” from 1921. The costumes and film were such a hit with fans that when the studio, Murray’s own Tiffany Pictures, was looking to produce talkies, they returned to the script and remade it in 1930. It marked Murray’s debut in talking pictures, but her career very quickly went downhill after the film was released.

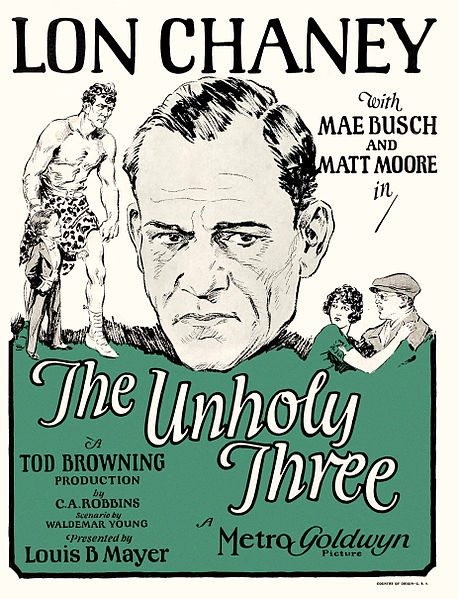

Tod Browning’s “The Unholy Three” received similar treatment following the introduction of film with sound. Originally released in 1925, the film starred the man of a thousand faces, Lon Chaney as Professor Echo. Chaney reprised his role in the 1930 remake, and marketers used this fact to drum up interest. Posters for the film proclaimed “Lon Chaney talks!” and audience flocked to theaters to hear him speak. By the time the film was released, Chaney was terminally ill with throat cancer, and the film featured his only speaking role.

Of course, silent films weren’t only remade by studios looking to make a quick buck. Some directors and actors used the concept of the remake as an opportunity to create something they felt was superior to their previous work. Such is the case with “Ben-Hur” and “The Ten Commandments.”

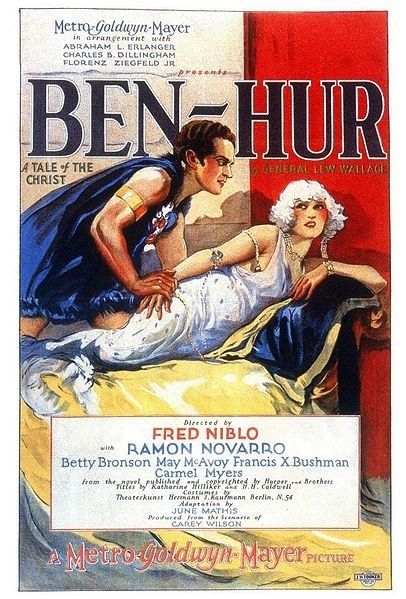

The hugely popular novel “Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ” was published in 1880 and very quickly became hot material for film. An early, and severely abridged, film adaptation was released in 1907, but when MGM acquired the rights to it in, it was approached as a story to be filmed on an epic scale. By the time it was released in 1925, its original director had been fired, it had been in production for two years and it was on record as the most expensive silent film ever made. Although the studio still lost money, the film was still very popular and very successful.

The chariot scene, in particular, became one of the most iconic scenes in silent film. So much so, in fact, that when the film was remade in 1959, the scene was recreated almost shot-for-shot. This was made easier by the fact that director William Wyler was actually an assistant director for the 1925 version.

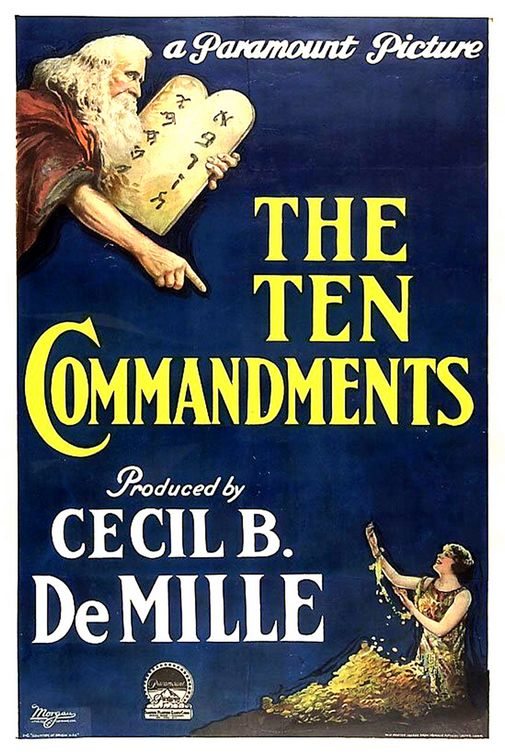

Cecil B. DeMille remains one of the most iconic directors of classic Hollywood, but he wasn’t above re-imagining his earlier work. When it was released in 1923, the silent version of “The Ten Commandments” was a grand spectacle of a film, but only partially dealt with the biblical tale. Taking a cue from D.W. Griffith, DeMille had set half of the film in biblical times and half in modern times. When DeMille set out to recreate the grandeur of the film, he abandoned the modern parable and focused entirely on the biblical tale. The 1953 remake of “The Ten Commandments” was incredibly successful and ended up being DeMille’s final film, serving as a fitting bookend to a career that spanned 40 years.

Cecil B. DeMille remains one of the most iconic directors of classic Hollywood, but he wasn’t above re-imagining his earlier work. When it was released in 1923, the silent version of “The Ten Commandments” was a grand spectacle of a film, but only partially dealt with the biblical tale. Taking a cue from D.W. Griffith, DeMille had set half of the film in biblical times and half in modern times. When DeMille set out to recreate the grandeur of the film, he abandoned the modern parable and focused entirely on the biblical tale. The 1953 remake of “The Ten Commandments” was incredibly successful and ended up being DeMille’s final film, serving as a fitting bookend to a career that spanned 40 years.

Of course, these are just a few of the many silent films that were remade as talkies — “The Littlest Rebel,” “Tess of the Storm Country,” “Daddy Long Legs” and “Way Down East” were all reimagined as talkies. Even “Brewster’s Millions,” which has been adapted to film several times, began as a silent film.

Check out the posters for the talkie versions of some of these films on our Silent Film Pinterest pinboard.

Want to dive deeper into the world of silent film? Keep up with my posts over on Curtains or on Chicago Nitrate.